2023: A Gift of Perspective

Exactly half-way through this year, I was in waiting for a potentially life-altering medical diagnosis. Long story short: months of worrying symptoms suddenly turned into a frightening episode. I was now contending with a potential diagnosis for a progressive degenerative condition that would lead to physical disability sooner or later.

Before I go any further, let me say that this didn’t end as badly. To the surprise of two separate specialist doctors who were sure of the condition, it was not it. Reflecting on this journey is more to do with what it did for me, rather than what it did to me.

What started as unusual symptoms suddenly snowballed into debilitating imbalance with me being unable to walk across the room in my own home, unable to keep my eyelids open, unable to even sit up to have dinner with my husband and son. From one day to the next, I was unable to go out on my own, let alone care for my son. I was practically a second child for Karthik to care for– a dependant. A future of decreasing ability felt all too imminent all at once. I seemed to be already living a version of it. Was this the beginning?

Between then and the agonising wait to get a concrete diagnosis, my mind was consumed by the utter helplessness my body felt. The sudden loss of autonomy called into question all of what I am: a mother to a young child, a partner, a sister, a friend, a daughter to aging parents, and then of course, a self-employed professional with ambition and plans. It took me little effort to go through all the ways in which I would become absent, unavailable, and maybe even invisible, in some instances, if my body continued this way. The realisation that there are people who live this as their reality on a daily basis, and for life, was quick, but also mind-numbing.

What pained me the most was thinking about what it would do to my future with my 3.5 year old son. To say that I was (am) carrying some baggage from my dual experience of the pandemic with new parenthood would be an understatement. The isolation created by the combination of the pandemic and new parenthood came at complete loggerheads with the need to preserve a long-nurtured career which suddenly turned fragile with motherhood. I shuddered at the thought. I was already struggling with enough guilt about the ratio of time I spent between my child and my work. What else would I start to miss now, because I might simply not be capable? I was absolutely not ready, in fact, falling apart with the thought of adding another constraint to the mix.

I’m not sure what exactly in the barrage of realisations triggered it, from one day to the next, my mental health plummeted and went into free fall. I’ve rolled with change all my life, and while I’m no champion at it, I’ve always gotten by. I could not fathom how unbelievably out of control I felt this time. Was this me, really?

I have been surrounded by disabled people all my life: my cousin in the village who never left her bed and then passed away at 40, my childhood music teacher who was blind and would commute with public transportation through the streets of Chennai to come teach my sister and I in our apartment, my dear friend from my Masters program in LA who drove my sister and I, while being in a wheelchair himself, to name a few close ones. I am an empathetic, loving friend who will do what I can to help support less-abled friends and family, but hell, I’d taken my ableism for granted. And how. It wasn’t unabashed arrogance, but still, a convenient assumption upon which my whole life view was built.

When the doctor finally called me in to discuss my results, my mind swayed between utter relief from a close shave to a very plausible future and utter dissonance to the surreality of it all. And while my self-talk immediately wants me to shame myself into thinking I completely lost a handle on the situation and that it was all in my head, that would in fact be an insult to the pure human truth.

This wasn’t about me at all.

It was a gift of perspective. A realisation of the privilege of being able-bodied. The privilege of not being left behind, thanks to pure luck. And the privilege to take it for granted.

It took a while to treat my physical symptoms. And that while gave me so much to think about, it shook me up from deep within. I’m humbled, grateful– and with deep, deep feeling for those living with disability. Up until the half of the year, I’d been wrestling with the kind of purpose I wanted to bring to my work– I was making progress unearthing and crystallising all of my experience and interests into an intersectional essence. As a brown person, and as a woman, I’ve had my share of exclusion, yet I’d never come this close to understanding what this specific layer of exclusion actually meant– despite those affected around me. I’m at a loss about this realisation. As a designer, I’m embarrassed I haven’t done or thought enough about it already.

It is clear what I want to do next. I’d like to actively work for the disabled community– I’m putting this out there into the universe. I can’t say I know enough of the space to be solving problems– in fact, all I have is only my projected feelings from my experience. But I have a hunch things are indeed as grim as they seemed. I want to learn and I want to be a part of the change. Research is an area I’d like to start with. If you know of a service, product or project tackling this and looking for a designer, I’m here. But it can also be an individual looking for support. I strongly believe in one on one relationships as much as I want to design for change at scale, so I’m here for both.

During one of those wild days, the therapist, who I’d scrambled to find in absolute emergency mode, told me, “…but you’re still fairly able-bodied. Do what you need to do while you can”. I found her words so banal, I could’ve pulled my hair out at that moment. “You’re no help”, I thought. But over the days, I understood the privilege of still having what I did. As I eventually recovered from the episode, small, everyday things like being able to carry my child, chasing him in the playground, standing at the stove to cook my family an indulgent dinner – I found magic in them.

Another gift came out of all of this.

Somewhere in those weeks of intense despair and emotional paralysis, a moment of clarity started to emerge. In a clearing of the mind (thanks to the anti-depressants I had to be on), I found a strange lucidity to truly grasp my priority list in life.

Of the progress of cognitive and physical disability I was learning about, I discovered that spasticity and loss of fine motor skills was inevitable. That broke me…as a designer, as a maker, as a cook, as a childhood artist. I held up my hands and looked at them. I have not even started to really use my hands, I thought to myself. Between having the rational mind of a designer and the raw instincts of my hands, without a moment of doubt, I knew what I’d pick. I wanted to honour the dormant potential in my hands– all I wanted to do now was to make and paint– and paint and make. I didn’t care about being clever and saying cool things. I wanted to my hands to live their life.

Thinking about my priority list, I went back to my random ramblings of 2023 projects I’d put down at the start of the year. A brain dump of sorts– some goals and some half-stream-of-consciousnessy things I wanted to do.

One thing always appeared on such lists. This time it stuck out.

A lifetime of desire to paint for fun, for amusement, for therapy, maybe even for a profession. All of which I have always ended up putting aside as an adult. Because time. Because money. Because does anyone care? Whatever, any number of excuses were always at the ready. And here it was. Again.

When I was a child, I was so sure I wanted to be a painter and then I talked myself out of it. But today, with the value of the should-dos dissipating away, what remained was that raw instinct– as it always was.

It does not look like my hands will lose their motor skills any time soon, not predictably anyway, but I am going to honour that moment of clarity. Another gift of perspective to learn from.

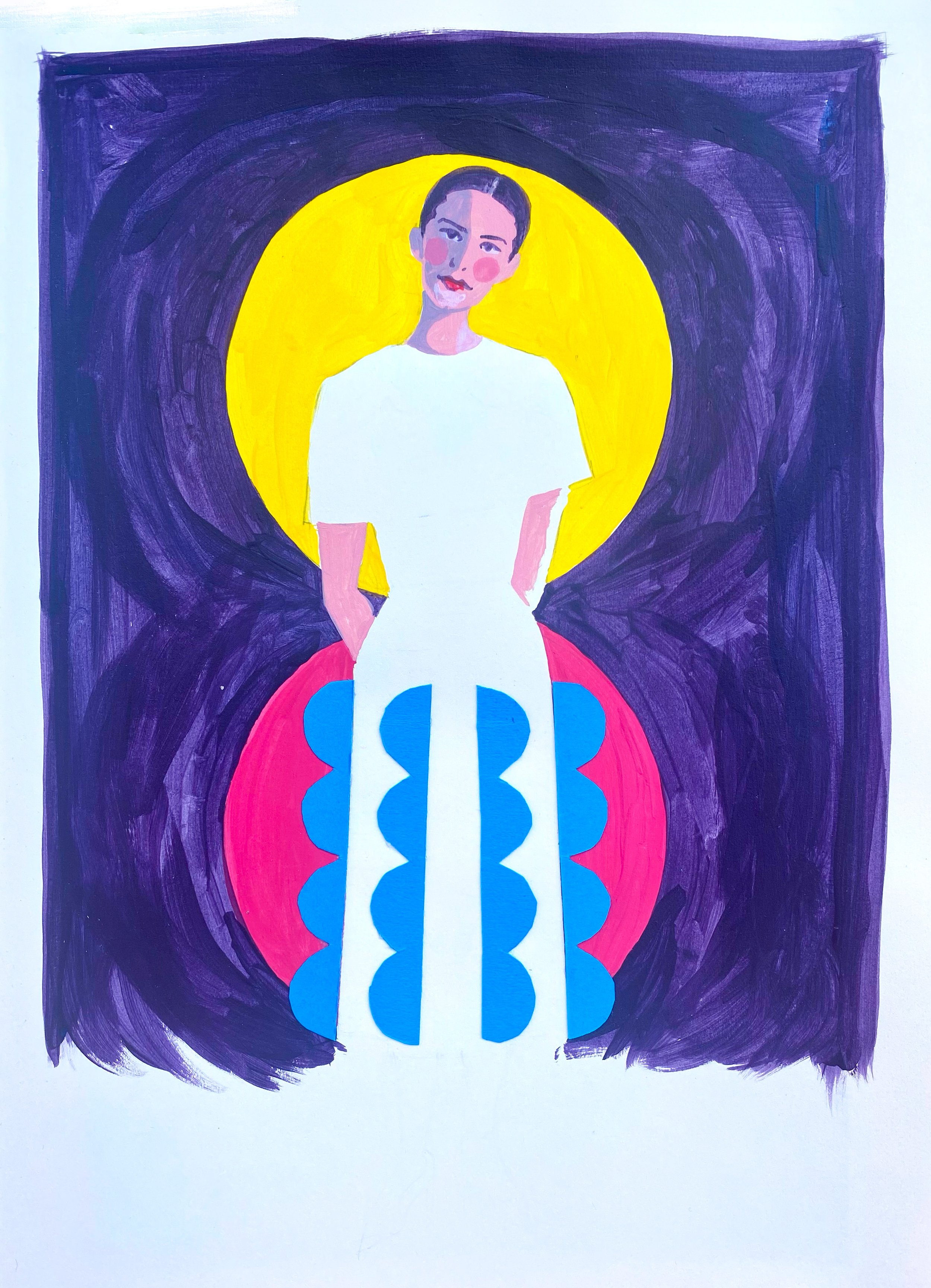

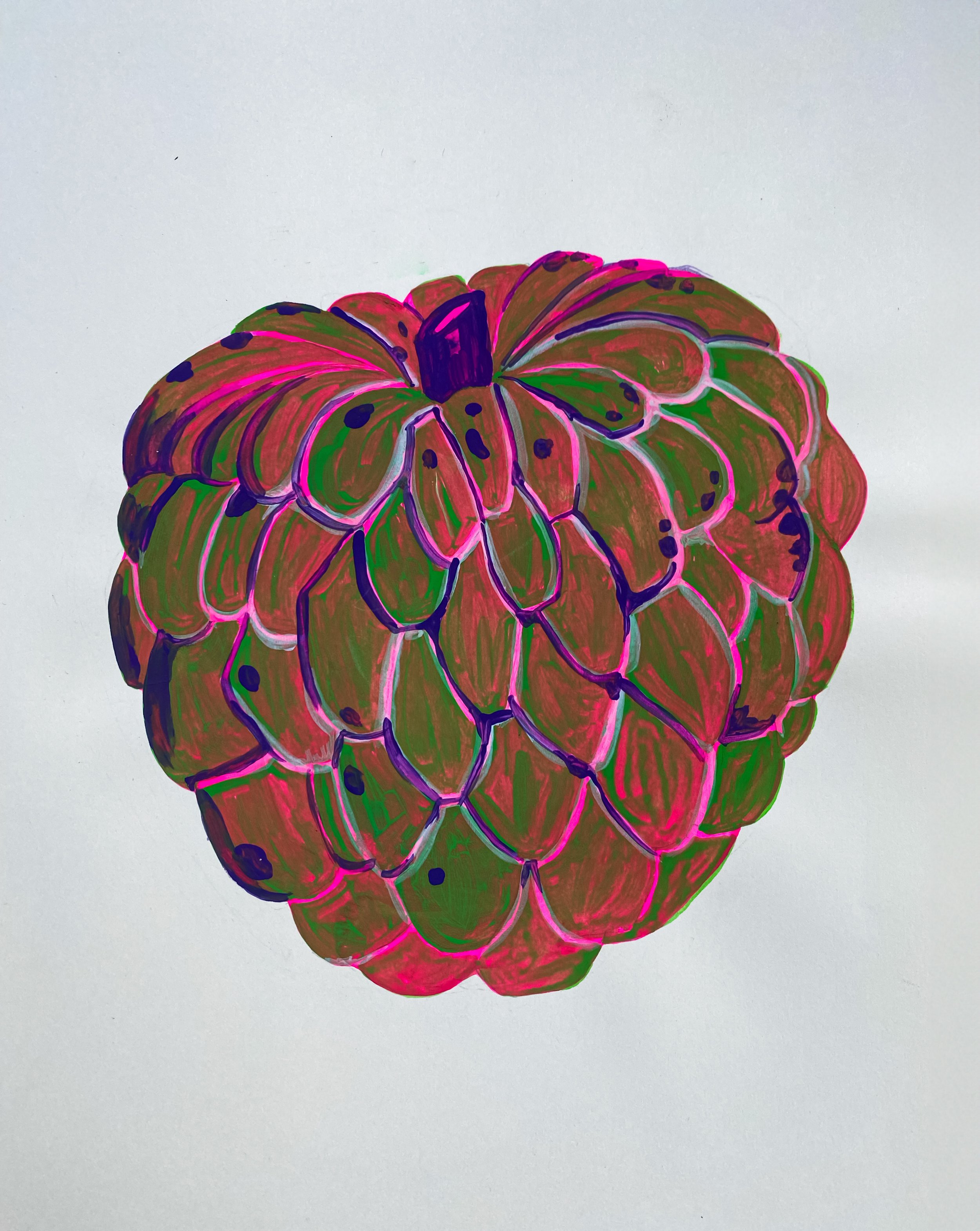

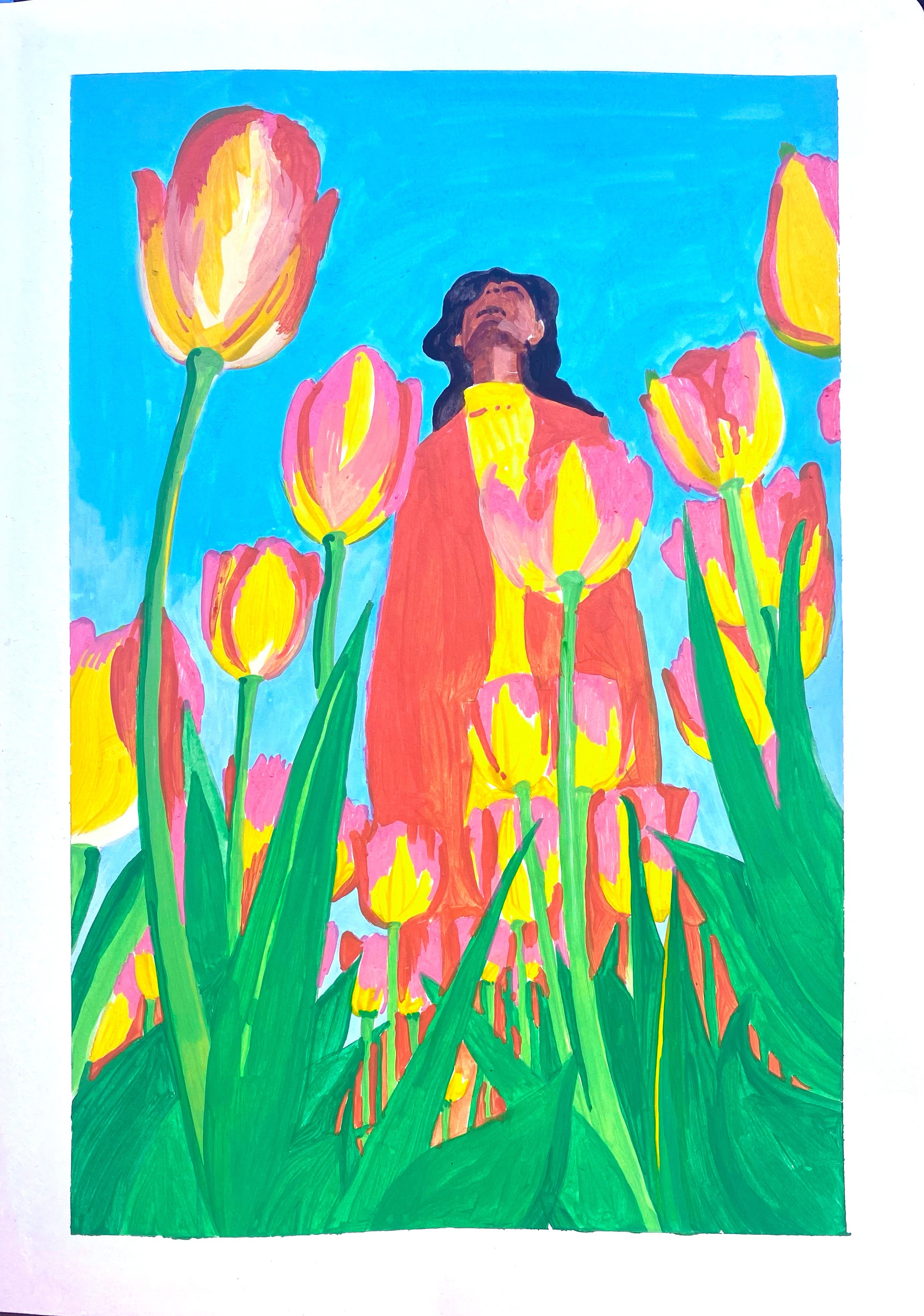

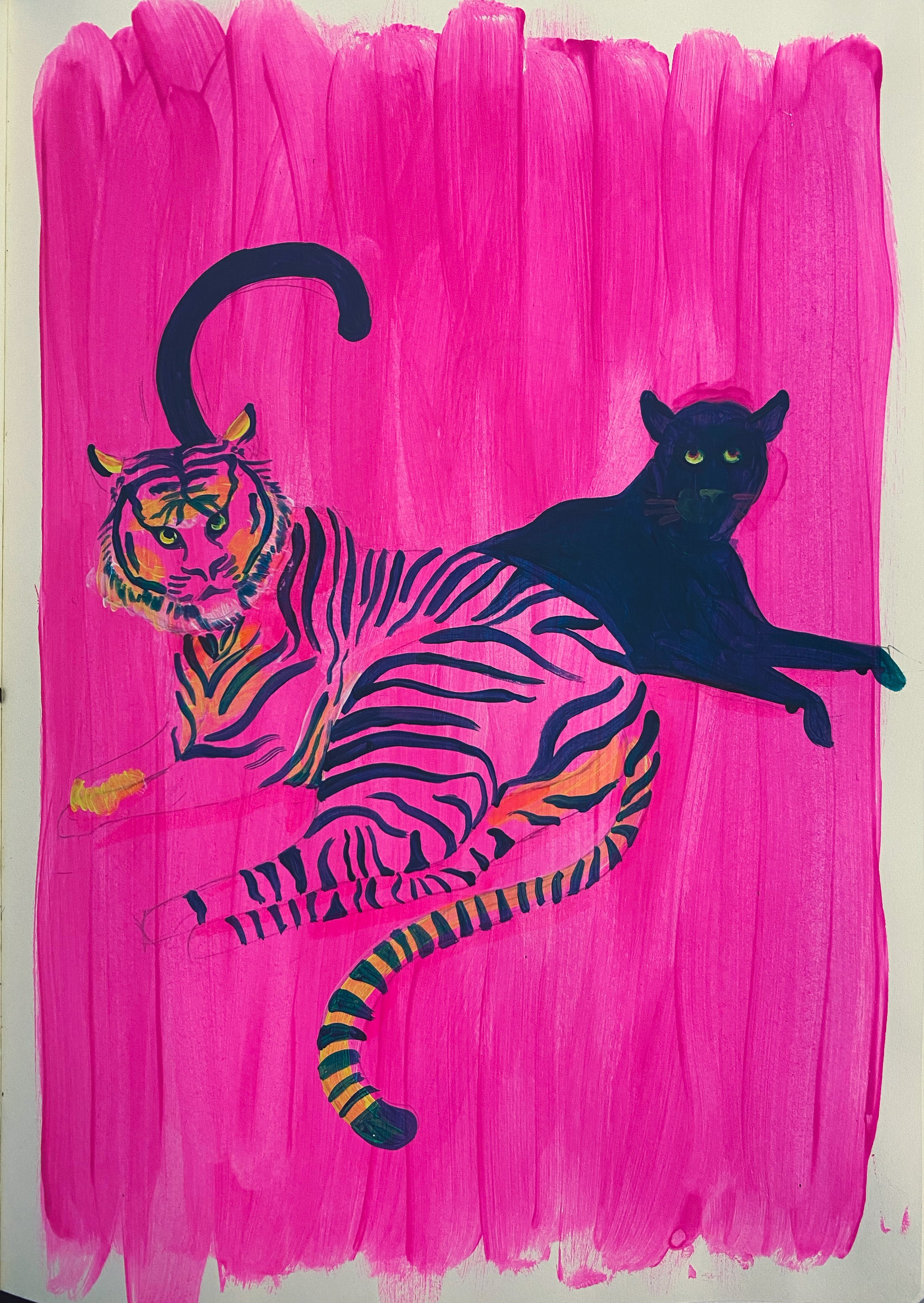

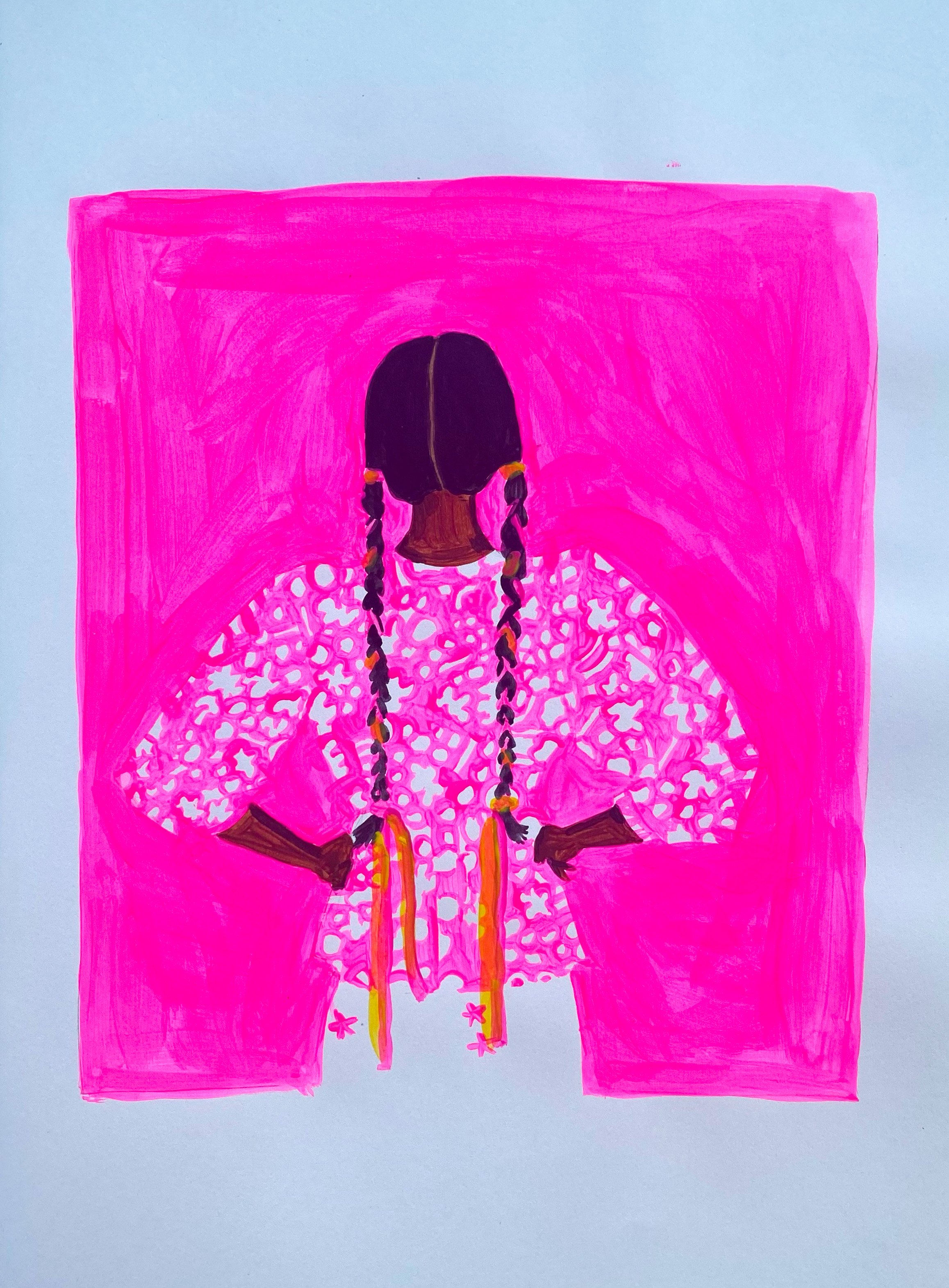

I decided to be methodical about this. I signed up for a mentorship with the amazing Riso Chan, who has since guided me through a process of exploring my painting voice. Her exercises have been a revelation– I could never have deconstructed patterns in my painting work on my own. I’m learning to lose any pretences and paint like no-one’s watching– a joyous yet meditative space (the process here can be an article on its own).

In the process of doing so, I managed to fill my sketchbook with about 40 paintings in a little over a month, astonishing myself in the process.

Nurturing a hobby as a parent has been very, very tough– so much so that I had started the year writing down “painting”, while already being okay with the fact that I’d probably never get around to it. But learning what I did this year, I finally got down to it every day, creating a ritual of it after my son went to bed. In fact, it slowly healed me from the wild emotional trip of the previous few months. Despite occasional breaks thanks to the real world (paying bills), I am eager to build this into a strong ritual for 2024.

Thank you for reading this far. It’s been intense trying to put all of this into words as I look back at 2023. I worked on a lot of projects– strategic, tactical, tangible things. It would’ve been much easier to write about them, but this felt far more important. Meanwhile, months later, the diagnosis is in fact still ongoing. I can’t decide if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but this hairy experience has already given me so much to think about, I feel profoundly grateful.

In some ways, it was more essential to write this out for myself. Because I want to be able to read this again and again and again in the future lest I forget the fallibility of human assumption and our expectations of a “normal” life unchallenged, unchanged by the very nature of being human. Here’s to a more inspired 2024!